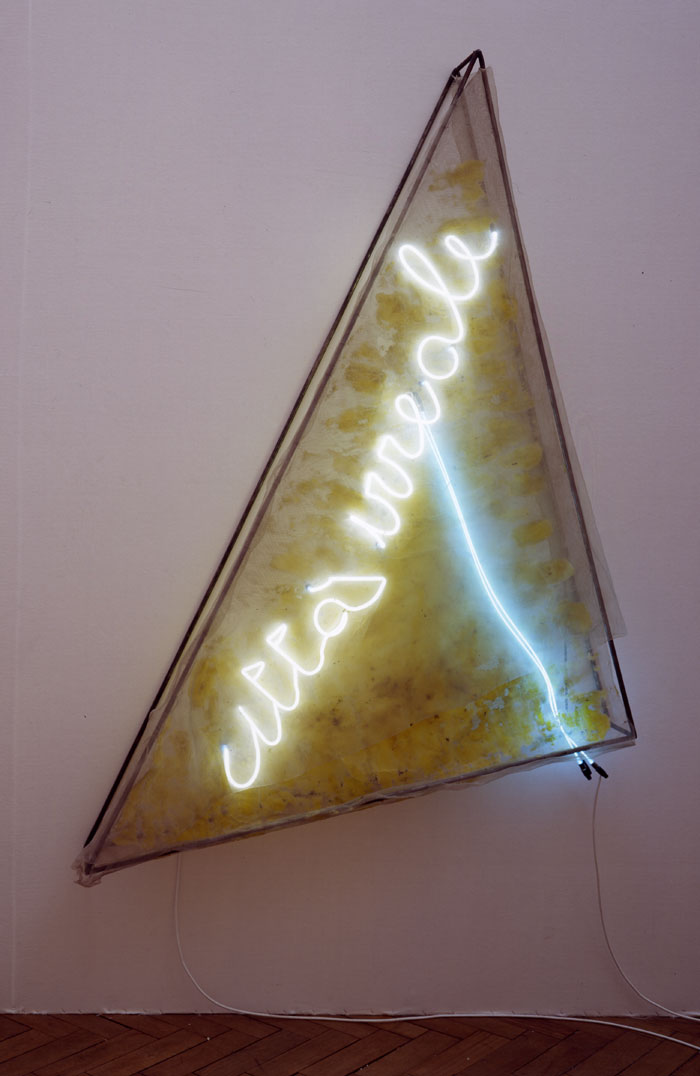

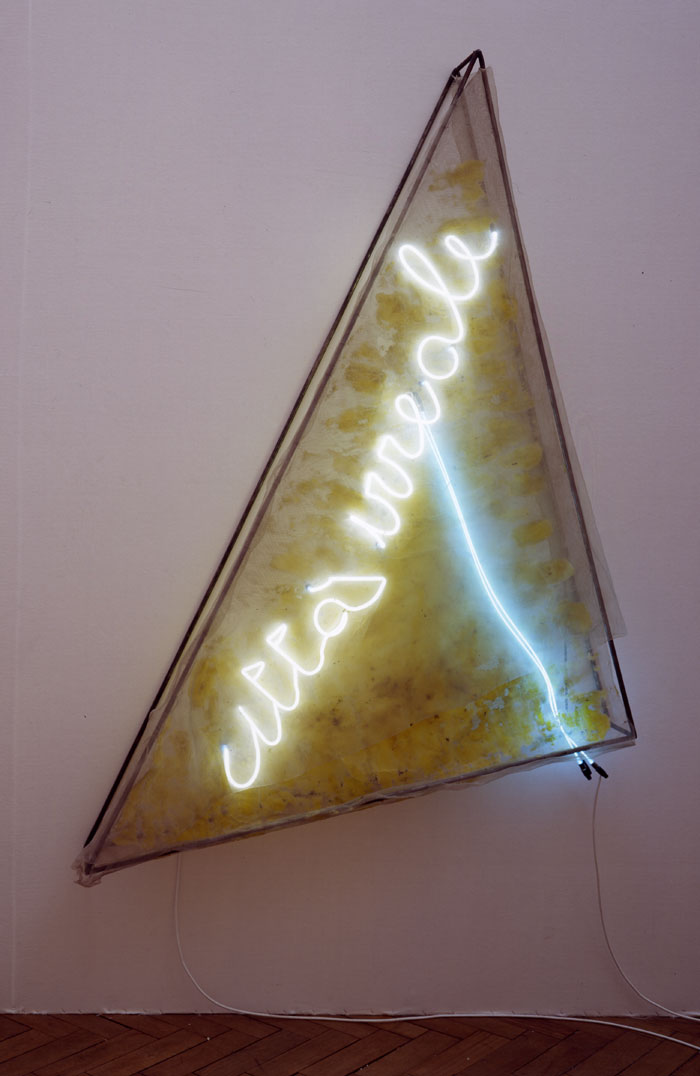

Mario Merz, Città irreale, 1968 | collection Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam

Piero Gilardi, Still Life of Watermelons (detail), 1967

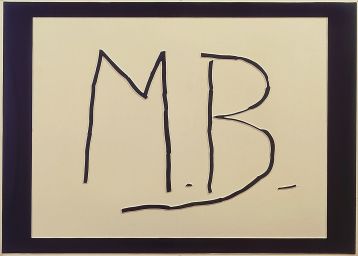

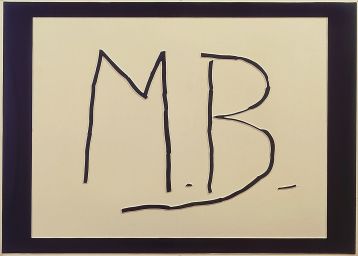

Marcel Broodthaers, M.B, 1970

project Conservation of Modern Art / Modern Art: Who Cares?

1995 -1997

In 1995 thirteen partners worked jointly on the development of models for the registration and preservation of contemporary art and on the testing of these in practice. This was based on a reassessment of the existing, traditional philosophies on conservation and an evaluation of new developments and points of view. The symposium drew 450 participants from all over the world. The results of the study and the symposium were published in Modern Art: Who Cares?, which has become an internationally recognized standard reference.

The conservation of contemporary art poses new and often complicated problems for museums. Twentieth-century artists use a wide variety of materials, giving them totally individual artistic meaning. Modern art differs from traditional art in that the significance of the materials and methods used is no longer clear-cut. This has far-reaching consequences for the preservation of contemporary art collections.

The following ten objects were selected for the Project ‘Conservation of Modern Art’.

— Mario Merz, Città irreale, 1968 | collection Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam

This suspended object consists of a triangular metal frame covered with gauze. Wax has been applied to the gauze. Neon tubes pushed through the gauze form the words ‘città irreale’. The neon tube is becoming discoloured, the beeswax is dis-integrating and the tulle discolours and breaks.

— Jean Tinguely, Gismo, 1960 | collection Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam

Tinguely's machine is made up of a large number of iron parts, including a rectangular framework and wheels of various sizes. There is evidence of rust formation, wear and loss of material and parts.

— Piero Gilardi, Still life of water melons, 1967 | collection Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen

The melon field, originally painted in bright colours, is made of foam plastic. The foam plastic has dried out. Any form of transport or contact may cause a piece to break off. An additional problem is that the object retains dust or perhaps even attracts it.

— Marcel Broodthaers, M.B, 1970 | collection Bonnefantenmuseum

The black letters M.B. are shown in relief on a pair of plastic plaques. One plaque has a black background, the other a white background. The plastic is degrading. The nature of the material is unknown. The plaques are suspended by means of small circular holes. Owing to the degradation of the plastic the holes are now very brittle; one has already broken.

— Tony Cragg, One space, four places, 1982 | collection Van Abbemuseum

The object represents a table and four chairs. This ‘furniture’ is made from many different kinds of waste materials, including various plastics and sponge. The materials used are rapidly disintegrating.

— Krijn Giezen, Morocco, 1972 | collection Frans Halsmuseum

The object is a chipboard cabinet covered with fabric and containing many different items, such as drawings, tools, a bird and a bunch of herbs. The items are attached with wire. Chipboard is acidic and is damaging the fabric, the wire is rusting and many of the items have disintegrated.

— Henk Peeters, 59-18, 1959 | collection Netherlands Institute for Cultural Heritage | ICN

The object is made of foam rubber, a material much used in the 60s and 70s. The foam rubber is degrading, as a result of which cracks have appeared.

— Woody van Amen, Ice machine, Willem Barentz's winter on Novaya Zemlya, 1969 | collection Centraal Museum Utrecht

The machine is a large cabinet made of aluminium and perspex. It contains: fluorescent tubes, mechanical parts, two compartments filled with hay, a freezing unit now no longer working, a perspex drip-tray and imitation wooden blocks. Insects might have got into the hay and the freezing unit is broken.

— Pino Pascali, Campi arati e canali di irrigazione, 1968 | collection Kröller- Müller Museum

The object consists of corrugated asbestos sheets, covered with a layer of earth, and iron basins filled with aniline blue water. Asbestos, used in the sheets, is carcinogenic; some of the basins are so rusty that they can no longer be filled with water.

— Manzoni, Achrome, 1962 | collection Kröller-Müller Museum

The Achrome consists of tufts of glass wool attached to polystyrene. The flat background is covered in red velvet. A perspex cover protects the work. Despite the cover, the glass wool has become very dirty: the hairs have stuck together. It is not clear whether the work can be cleaned and if so how this should be done.

History

In 1990 the Dutch government launched a ‘rescue operation’ known as the Deltaplan for the Preservation of Culutural Heritage in order to catch up on lagging development related tot the preservation and maintenance of cultural heritage. Museums were given the task of ascertaining inadequacies and establishing priorities. Introducing objective standards in order to determine the condition of modern and contemporary art proved, however, to be difficult. Curators and conservators made inquiries among colleagues, within the country and abroad, and discoverd that little research had been done on modern materials, methods of treatments and decisionmaking about this. There arose discussons on authenticitiy, the relationship between menaing and the use of material, conservation ethics and the importance of information about material and working methods of the artists themselves. A considerable number of Dutch museums were involved in these discussions, and this gave rise to an informal network. The Foundation for the Conservation of Contemporary Art (SBMK) was set up in 1995 as a means of formalizing the informal consultations, stimulating (inter)natonal) collaboration and allowing it to develop further within an official framework.